Darryl D'Lima, an orthopedic specialist, worked with a bioprinter in his research on cartilage at Scripps Clinic in San Diego. Dr. D’Lima, who heads an orthopedic research lab at the Scripps Clinic here, has already made bioartificial cartilage in cow tissue, modifying an old inkjet printer to put down layer after layer of a gel containing living cells. He has also printed cartilage in tissue removed from patients who have undergone knee replacement surgery. There is much work to do to perfect the process, get regulatory approvals and conduct clinical trials, but his eventual goal sounds like something from science fiction: to have a printer in the operating room that could custom-print new cartilage directly in the body to repair or replace tissue that is missing because of injury or arthritis. Just as 3-D printers have gained in popularity among hobbyists and companies who use them to create everyday objects, prototypes and spare parts (and even a crude gun), there has been a rise in interest in using similar technology in medicine. Instead of the plastics or powders used in conventional 3-D printers to build an object layer by layer, so-called bioprinters print cells, usually in a liquid or gel. The goal isn’t to create a widget or a toy, but to assemble living tissue. At labs around the world, researchers have been experimenting with bioprinting, first just to see whether it was possible to push cells through a printhead without killing them (in most cases it is), and then trying to make cartilage, bone, skin, blood vessels, small bits of liver and other tissues. There are other ways to try to “engineer” tissue — one involves creating a scaffold out of plastics or other materials and adding cells to it. In theory, at least, a bioprinter has advantages in that it can control the placement of cells and other components to mimic natural structures. But just as the claims made for 3-D printing technology sometimes exceed the reality, the field of bioprinting has seen its share of hype. News releases, TED talks and news reports often imply that the age of print-on-demand organs is just around the corner. (Accompanying illustrations can be fanciful as well — one shows a complete heart, seemingly filled with blood, as the end product in a printer). The reality is that, although bioprinting researchers have made great strides, there are many formidable obstacles to overcome. “Nobody who has any credibility claims they can print organs, or believes in their heart of hearts that that will happen in the next 20 years,” said Brian Derby, a researcher at the University of Manchester in Britain who reviewed the field last year in an article in the journal Science. For now, researchers have set their sights lower. Organovo, for instance, a San Diego company that has developed a bioprinter, is making strips of liver tissue, about 20 cells thick, that it says could be used to test drugs under development. A lab at the Hannover Medical School in Germany is one of several experimenting with 3-D printing of skin cells; another German lab has printed sheets of heart cells that might some day be used as patches to help repair damage from heart attacks. A researcher at the University of Texas at El Paso, Thomas Boland, has developed a method to print fat tissue that may someday be used to create small implants for women who have had breast lumpectomies. Dr. Boland has also done much of the basic research on bioprinting technologies. “I think it is the future for regenerative medicine,” he said. Dr. D’Lima acknowledges that his dream of a cartilage printer — perhaps a printhead attached to a robotic arm for precise positioning — is years away. But he thinks the project has more chance of becoming reality than some others. “Printing a whole heart or a whole bladder is glamorous and exciting,” he said. “But cartilage might be the low-hanging fruit to get 3-D printing into the clinic.” One reason, he said, is that cartilage is in some ways simpler than other tissues. Cells called chondrocytes sit in a matrix of fibrous collagens and other compounds secreted by the cells. As cells go, chondrocytes are relatively low maintenance — they do not need much nourishment, which simplifies the printing process.

Darryl D'Lima, an orthopedic specialist, worked with a bioprinter in his research on cartilage at Scripps Clinic in San Diego. Dr. D’Lima, who heads an orthopedic research lab at the Scripps Clinic here, has already made bioartificial cartilage in cow tissue, modifying an old inkjet printer to put down layer after layer of a gel containing living cells. He has also printed cartilage in tissue removed from patients who have undergone knee replacement surgery. There is much work to do to perfect the process, get regulatory approvals and conduct clinical trials, but his eventual goal sounds like something from science fiction: to have a printer in the operating room that could custom-print new cartilage directly in the body to repair or replace tissue that is missing because of injury or arthritis. Just as 3-D printers have gained in popularity among hobbyists and companies who use them to create everyday objects, prototypes and spare parts (and even a crude gun), there has been a rise in interest in using similar technology in medicine. Instead of the plastics or powders used in conventional 3-D printers to build an object layer by layer, so-called bioprinters print cells, usually in a liquid or gel. The goal isn’t to create a widget or a toy, but to assemble living tissue. At labs around the world, researchers have been experimenting with bioprinting, first just to see whether it was possible to push cells through a printhead without killing them (in most cases it is), and then trying to make cartilage, bone, skin, blood vessels, small bits of liver and other tissues. There are other ways to try to “engineer” tissue — one involves creating a scaffold out of plastics or other materials and adding cells to it. In theory, at least, a bioprinter has advantages in that it can control the placement of cells and other components to mimic natural structures. But just as the claims made for 3-D printing technology sometimes exceed the reality, the field of bioprinting has seen its share of hype. News releases, TED talks and news reports often imply that the age of print-on-demand organs is just around the corner. (Accompanying illustrations can be fanciful as well — one shows a complete heart, seemingly filled with blood, as the end product in a printer). The reality is that, although bioprinting researchers have made great strides, there are many formidable obstacles to overcome. “Nobody who has any credibility claims they can print organs, or believes in their heart of hearts that that will happen in the next 20 years,” said Brian Derby, a researcher at the University of Manchester in Britain who reviewed the field last year in an article in the journal Science. For now, researchers have set their sights lower. Organovo, for instance, a San Diego company that has developed a bioprinter, is making strips of liver tissue, about 20 cells thick, that it says could be used to test drugs under development. A lab at the Hannover Medical School in Germany is one of several experimenting with 3-D printing of skin cells; another German lab has printed sheets of heart cells that might some day be used as patches to help repair damage from heart attacks. A researcher at the University of Texas at El Paso, Thomas Boland, has developed a method to print fat tissue that may someday be used to create small implants for women who have had breast lumpectomies. Dr. Boland has also done much of the basic research on bioprinting technologies. “I think it is the future for regenerative medicine,” he said. Dr. D’Lima acknowledges that his dream of a cartilage printer — perhaps a printhead attached to a robotic arm for precise positioning — is years away. But he thinks the project has more chance of becoming reality than some others. “Printing a whole heart or a whole bladder is glamorous and exciting,” he said. “But cartilage might be the low-hanging fruit to get 3-D printing into the clinic.” One reason, he said, is that cartilage is in some ways simpler than other tissues. Cells called chondrocytes sit in a matrix of fibrous collagens and other compounds secreted by the cells. As cells go, chondrocytes are relatively low maintenance — they do not need much nourishment, which simplifies the printing process. Tuesday, 20 August 2013

At the Printer, Living Tissue

Darryl D'Lima, an orthopedic specialist, worked with a bioprinter in his research on cartilage at Scripps Clinic in San Diego. Dr. D’Lima, who heads an orthopedic research lab at the Scripps Clinic here, has already made bioartificial cartilage in cow tissue, modifying an old inkjet printer to put down layer after layer of a gel containing living cells. He has also printed cartilage in tissue removed from patients who have undergone knee replacement surgery. There is much work to do to perfect the process, get regulatory approvals and conduct clinical trials, but his eventual goal sounds like something from science fiction: to have a printer in the operating room that could custom-print new cartilage directly in the body to repair or replace tissue that is missing because of injury or arthritis. Just as 3-D printers have gained in popularity among hobbyists and companies who use them to create everyday objects, prototypes and spare parts (and even a crude gun), there has been a rise in interest in using similar technology in medicine. Instead of the plastics or powders used in conventional 3-D printers to build an object layer by layer, so-called bioprinters print cells, usually in a liquid or gel. The goal isn’t to create a widget or a toy, but to assemble living tissue. At labs around the world, researchers have been experimenting with bioprinting, first just to see whether it was possible to push cells through a printhead without killing them (in most cases it is), and then trying to make cartilage, bone, skin, blood vessels, small bits of liver and other tissues. There are other ways to try to “engineer” tissue — one involves creating a scaffold out of plastics or other materials and adding cells to it. In theory, at least, a bioprinter has advantages in that it can control the placement of cells and other components to mimic natural structures. But just as the claims made for 3-D printing technology sometimes exceed the reality, the field of bioprinting has seen its share of hype. News releases, TED talks and news reports often imply that the age of print-on-demand organs is just around the corner. (Accompanying illustrations can be fanciful as well — one shows a complete heart, seemingly filled with blood, as the end product in a printer). The reality is that, although bioprinting researchers have made great strides, there are many formidable obstacles to overcome. “Nobody who has any credibility claims they can print organs, or believes in their heart of hearts that that will happen in the next 20 years,” said Brian Derby, a researcher at the University of Manchester in Britain who reviewed the field last year in an article in the journal Science. For now, researchers have set their sights lower. Organovo, for instance, a San Diego company that has developed a bioprinter, is making strips of liver tissue, about 20 cells thick, that it says could be used to test drugs under development. A lab at the Hannover Medical School in Germany is one of several experimenting with 3-D printing of skin cells; another German lab has printed sheets of heart cells that might some day be used as patches to help repair damage from heart attacks. A researcher at the University of Texas at El Paso, Thomas Boland, has developed a method to print fat tissue that may someday be used to create small implants for women who have had breast lumpectomies. Dr. Boland has also done much of the basic research on bioprinting technologies. “I think it is the future for regenerative medicine,” he said. Dr. D’Lima acknowledges that his dream of a cartilage printer — perhaps a printhead attached to a robotic arm for precise positioning — is years away. But he thinks the project has more chance of becoming reality than some others. “Printing a whole heart or a whole bladder is glamorous and exciting,” he said. “But cartilage might be the low-hanging fruit to get 3-D printing into the clinic.” One reason, he said, is that cartilage is in some ways simpler than other tissues. Cells called chondrocytes sit in a matrix of fibrous collagens and other compounds secreted by the cells. As cells go, chondrocytes are relatively low maintenance — they do not need much nourishment, which simplifies the printing process.

Darryl D'Lima, an orthopedic specialist, worked with a bioprinter in his research on cartilage at Scripps Clinic in San Diego. Dr. D’Lima, who heads an orthopedic research lab at the Scripps Clinic here, has already made bioartificial cartilage in cow tissue, modifying an old inkjet printer to put down layer after layer of a gel containing living cells. He has also printed cartilage in tissue removed from patients who have undergone knee replacement surgery. There is much work to do to perfect the process, get regulatory approvals and conduct clinical trials, but his eventual goal sounds like something from science fiction: to have a printer in the operating room that could custom-print new cartilage directly in the body to repair or replace tissue that is missing because of injury or arthritis. Just as 3-D printers have gained in popularity among hobbyists and companies who use them to create everyday objects, prototypes and spare parts (and even a crude gun), there has been a rise in interest in using similar technology in medicine. Instead of the plastics or powders used in conventional 3-D printers to build an object layer by layer, so-called bioprinters print cells, usually in a liquid or gel. The goal isn’t to create a widget or a toy, but to assemble living tissue. At labs around the world, researchers have been experimenting with bioprinting, first just to see whether it was possible to push cells through a printhead without killing them (in most cases it is), and then trying to make cartilage, bone, skin, blood vessels, small bits of liver and other tissues. There are other ways to try to “engineer” tissue — one involves creating a scaffold out of plastics or other materials and adding cells to it. In theory, at least, a bioprinter has advantages in that it can control the placement of cells and other components to mimic natural structures. But just as the claims made for 3-D printing technology sometimes exceed the reality, the field of bioprinting has seen its share of hype. News releases, TED talks and news reports often imply that the age of print-on-demand organs is just around the corner. (Accompanying illustrations can be fanciful as well — one shows a complete heart, seemingly filled with blood, as the end product in a printer). The reality is that, although bioprinting researchers have made great strides, there are many formidable obstacles to overcome. “Nobody who has any credibility claims they can print organs, or believes in their heart of hearts that that will happen in the next 20 years,” said Brian Derby, a researcher at the University of Manchester in Britain who reviewed the field last year in an article in the journal Science. For now, researchers have set their sights lower. Organovo, for instance, a San Diego company that has developed a bioprinter, is making strips of liver tissue, about 20 cells thick, that it says could be used to test drugs under development. A lab at the Hannover Medical School in Germany is one of several experimenting with 3-D printing of skin cells; another German lab has printed sheets of heart cells that might some day be used as patches to help repair damage from heart attacks. A researcher at the University of Texas at El Paso, Thomas Boland, has developed a method to print fat tissue that may someday be used to create small implants for women who have had breast lumpectomies. Dr. Boland has also done much of the basic research on bioprinting technologies. “I think it is the future for regenerative medicine,” he said. Dr. D’Lima acknowledges that his dream of a cartilage printer — perhaps a printhead attached to a robotic arm for precise positioning — is years away. But he thinks the project has more chance of becoming reality than some others. “Printing a whole heart or a whole bladder is glamorous and exciting,” he said. “But cartilage might be the low-hanging fruit to get 3-D printing into the clinic.” One reason, he said, is that cartilage is in some ways simpler than other tissues. Cells called chondrocytes sit in a matrix of fibrous collagens and other compounds secreted by the cells. As cells go, chondrocytes are relatively low maintenance — they do not need much nourishment, which simplifies the printing process. Bare Trees Are a Lingering Sign of Hurricane Sandy’s High Toll

Copper Facts Quiz

People have been living with copper for thousands of years. Ancient man pounded bits of native copper out of rocks to make tools and jewelry. Eventually we learned to smelt copper from ore and changed civilization enough to start the 'Copper Age' and we were on our way.

People have been living with copper for thousands of years. Ancient man pounded bits of native copper out of rocks to make tools and jewelry. Eventually we learned to smelt copper from ore and changed civilization enough to start the 'Copper Age' and we were on our way. Today, copper is in our water pipes, house wiring, cookware and even coins. Test your knowledge of our friend copper with this fun ten question quiz.

Drain Cleaner Can Dissolve Glass

Just about everyone knows many acids are corrosive. For example, hydrofluoric acid can dissolve glass (a chemical you do not want to mess with). Did you know strong bases can be corrosive, too? An example of a base sufficiently corrosive to eat glass is sodium hydroxide (NaOH), which is a common solid drain cleaner. You can test this for yourself by setting a glass container in hot sodium hydroxide, but you need to be extremely careful. Sodium hydroxide is perfectly capable of dissolving your skin in addition to glass. Also, it reacts with other chemicals, so you have be certain you perform this project in a steel or iron container. Test the container with a magnet if you are unsure, because the other metal commonly used in pans, aluminum, reacts vigorously with sodium hydroxide.

Just about everyone knows many acids are corrosive. For example, hydrofluoric acid can dissolve glass (a chemical you do not want to mess with). Did you know strong bases can be corrosive, too? An example of a base sufficiently corrosive to eat glass is sodium hydroxide (NaOH), which is a common solid drain cleaner. You can test this for yourself by setting a glass container in hot sodium hydroxide, but you need to be extremely careful. Sodium hydroxide is perfectly capable of dissolving your skin in addition to glass. Also, it reacts with other chemicals, so you have be certain you perform this project in a steel or iron container. Test the container with a magnet if you are unsure, because the other metal commonly used in pans, aluminum, reacts vigorously with sodium hydroxide. The sodium hydroxide reacts with the silicon dioxide in glass to form sodium silicate and water:

2NaOH + SiO2 ? Na2SiO3 + H2O

Dissolving glass in molten sodium hydroxide probably won't do your pan any favors, so chances are you'll want to throw it out when you are done. Neutralize the sodium hydroxide with an acid before disposing of the pan or attempting to clean it. If you don't have access to a chemistry lab, this could be achieved with a whole lot of vinegar (weak acetic acid) or a smaller volume of muriatic acid (hydrochloric), or (since it's drain cleaner, after all), you can wash the sodium hydroxide away with lots and lots of water.

You may not be interested in destroying glassware for science, but it's still worth knowing why it is important to remove dishes from your sink if you are planning to use solid drain cleaner and why it's not a good idea to use more than the recommended amount of the product.

Observatory: Software That Exposes Faked Photos

Using algorithms designed to sniff out suspicious shadows, computer scientists from Dartmouth and the University of California, Berkeley, say they have developed software that can reliably detect fake or altered photos. The technique could be useful in the emerging field of photo forensics, said Hany Farid, a Dartmouth computer science professor and developer of the software. In the age of Photoshop, detecting manipulated photos is a growing priority for lawyers, journalists and people involved in law enforcement and national security. To determine an image’s authenticity, the software uses geometric formulas to detect and analyze shadows that are invisible to the naked eye, then lines them up with a potential light source. If it cannot do so, it deems the image to be physically implausible. Analyzing shadows is a common technique in photo forensics, said the study, being published in the September issue of ACM Transactions on Graphics. But the eye simply cannot compete with the sophistication of today’s image-manipulation software. “Perceptual studies show that the brain is largely insensitive to gross inconsistencies in shadows,” Dr. Farid said. “That means that an analyst may not be very good at determining whether shadows are real or not. But more importantly, it means a forger may not notice when he or she places an incorrect shadow on an image.” To demonstrate the software, the researchers ran an analysis of a picture of the 1969 moon landing. They determined that the image was not a fake.

Using algorithms designed to sniff out suspicious shadows, computer scientists from Dartmouth and the University of California, Berkeley, say they have developed software that can reliably detect fake or altered photos. The technique could be useful in the emerging field of photo forensics, said Hany Farid, a Dartmouth computer science professor and developer of the software. In the age of Photoshop, detecting manipulated photos is a growing priority for lawyers, journalists and people involved in law enforcement and national security. To determine an image’s authenticity, the software uses geometric formulas to detect and analyze shadows that are invisible to the naked eye, then lines them up with a potential light source. If it cannot do so, it deems the image to be physically implausible. Analyzing shadows is a common technique in photo forensics, said the study, being published in the September issue of ACM Transactions on Graphics. But the eye simply cannot compete with the sophistication of today’s image-manipulation software. “Perceptual studies show that the brain is largely insensitive to gross inconsistencies in shadows,” Dr. Farid said. “That means that an analyst may not be very good at determining whether shadows are real or not. But more importantly, it means a forger may not notice when he or she places an incorrect shadow on an image.” To demonstrate the software, the researchers ran an analysis of a picture of the 1969 moon landing. They determined that the image was not a fake. This Day in Science History - August 19 - John Flamsteed

He used his own money to equip the observatory and perform his task of creating the star catalog. This would later cause a rift between himself and the Royal Society's president, Issac Newton. Newton wanted access to Flamsteed's data on lunar orbits for his Principia. Flamsteed did not want to release his data until it was complete but gave Newton the information with the understanding it was to be for his use only. Newton got Edmund Halley to publish Flamsteed's star catalog without his knowledge. Newton felt that any data gathered by the Royal Observatory belonged to the Royal Society and he could publish without Flamsteed's consent. Flamsteed felt the data belonged to him since he did the work with his instruments and the tables were incomplete. Flamsteed managed to collect 300 of the 400 copies of Halley's publication and publicly burned them.

Flamsteed would eventually release his tables before his death in 1719. It was later determined his tables contained a star he named 34 Tauri which would be the earliest observation of the planet Uranus. Find out what else occurred on this day in science history.

Follow About.com Chemistry on Facebook or Twitter.

Crowdsourcing, for the Birds

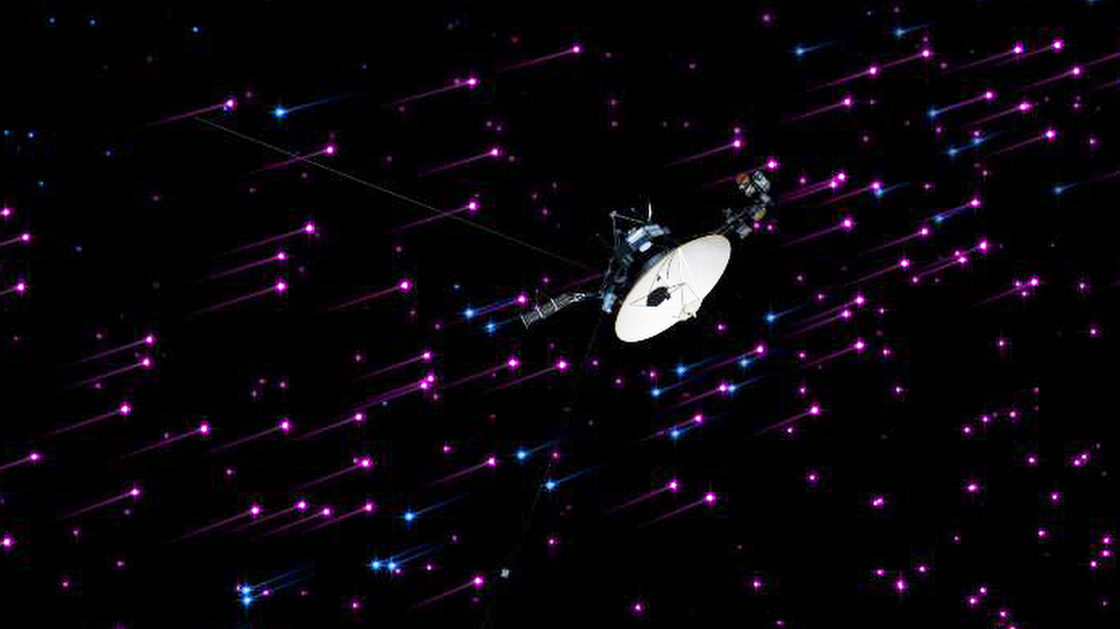

Has Voyager 1 Left The Solar System?

This artist rendering provided by NASA shows Voyager 1 at the edge of the solar system.

AP This artist rendering provided by NASA shows Voyager 1 at the edge of the solar system.AP

This artist rendering provided by NASA shows Voyager 1 at the edge of the solar system.AP The Voyager 1 spacecraft launched in 1977 on a mission to Jupiter and Saturn. It kept on going. Today it's billions of miles from Earth, and scientists have been predicting it will soon leave the solar system.

NPR has been on Voyager watch since at least 2003, when longtime science correspondent Richard Harris provided this warning of Voyager's impending departure.

But now Marc Swisdak, a physicist at the University of Maryland, says the spacecraft may have already left. "Late July 2012 is when we think it [left]," he says.

How did we miss that? As it turns out, it wasn't entirely our fault. Researchers thought the solar system was surrounded by a clearly marked magnetic field bubble.

This NASA diagram shows the two Voyager spacecraft inside the magnetic bubble around the sun. But Marc Swisdak believes it's already crossed the heliopause into interstellar space.

NASA This NASA diagram shows the two Voyager spacecraft inside the magnetic bubble around the sun. But Marc Swisdak believes it's already crossed the heliopause into interstellar space.NASA

This NASA diagram shows the two Voyager spacecraft inside the magnetic bubble around the sun. But Marc Swisdak believes it's already crossed the heliopause into interstellar space.NASA "There's one at the Earth, there's one at Jupiter, Saturn — many planets have them. And so just by analogy we were expecting there to be something like that for the solar system," Swisdak says.

Scientists were waiting for Voyager to cross over the magnetic edge of our solar system and into the magnetic field of interstellar space. But in a paper in the September issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters, Swisdak and his colleagues say the magnetic fields may blend together. And so in July 2012, when Voyager crossed from the solar system into deep space, "Voyager just kept cruising along," Swisdak says. All scientists saw was a change in the field's direction.

But not everyone thinks Voyager has left. Ed Stone is NASA's chief scientist for Voyager. He thinks there is a magnetic edge to the solar system, and until Voyager sees a change in the magnetic field, it hasn't left the solar system. He's hoping that change will come in the next few years.

"I think that there is a very good chance before we run out of electrical power that we will be demonstrably in interstellar space," he says.

Until Voyager's power goes out or the magnetic field flips, the scientific debate will continue. So will Voyager's journey, Swisdak says: "Basically it's just happily heading out toward ... pretty much nowhere."

Q&A: The Wild Past of Domestic Cats

This Day in Science History - August 20 - Werner Forssmann

This stunt earned him the ire of his superiors and he faced disciplinary action and changed his internship to urology. During World War II, he served in the German army as a doctor until he was captured and sat out the war in a prisoner of war camp. After the war, he worked as a lumberjack and country doctor until in 1956 he was surprised to receive part of the 1956 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his medical school "stunt".

Find out what else occurred on this day in science history.

Follow About.com Chemistry on Facebook or Twitter.

Why Carbon Dioxide Isn't an Organic Compound

If organic chemistry is the study of carbon, then why isn't carbon dioxide considered to be an organic compound? The answer is because organic molecules don't just contain carbon. They contain hydrocarbons or carbon bonded to hydrogen. The C-H bond has a lower bond energy than the carbon-oxygen bond in carbon dioxide, making carbon dioxide more stable/less reactive than the typical organic compound. So, when you're determining whether a carbon compound is organic or not, look to see whether it contains hydrogen in addition to carbon and whether the carbon is bonded to the hydrogen. Make sense?

If organic chemistry is the study of carbon, then why isn't carbon dioxide considered to be an organic compound? The answer is because organic molecules don't just contain carbon. They contain hydrocarbons or carbon bonded to hydrogen. The C-H bond has a lower bond energy than the carbon-oxygen bond in carbon dioxide, making carbon dioxide more stable/less reactive than the typical organic compound. So, when you're determining whether a carbon compound is organic or not, look to see whether it contains hydrogen in addition to carbon and whether the carbon is bonded to the hydrogen. Make sense? Intro to Organic Chemistry | List of Organic Compounds

How One Plus One Became Everything: A Puzzle of Life

It's one of life's great mysteries ...

Four billion years ago, or thereabouts, organic chemicals in the sea somehow spun themselves into little homes, with insides and outsides. We call them cells.

They did this in different ways, but always keeping their insides in, protected from the outside world ...

... surrounded by walls or skins of different types ...

... but letting in essentials, nutrients. Some even learned to eat sunshine, capturing energy ...

... which gave them a pulse of their own ...

... so they could move ...

.... and glow ...

Over time, they became more complicated ...

But though all this began 4 billion years ago, for some reason, and nobody knows why, all these cells, billions, trillions of them, didn't do the next obvious thing. They didn't link up.

It seems so simple. There's one of you. Why not join with another? Multicellular life has so many advantages; it not only makes you bigger and stronger, it allows you to do several things at once, complicated things like seeing or swimming or ... eventually, thinking and loving.

"More complexity was possible," writes Richard Fortey in his classic book Life, but for a puzzlingly long time — more than 70 percent of life's history on earth, all living things did was stay alone and divide. Why did it take so long for 1 plus 1 to begin? Why did it start? What changed?

The truth is, we don't know.

The mystery persists.

I asked digital artist Paolo Ceric to let me appropriate his elegant gifs for this essay. Paolo is currently a student in Zagreb, studying information processing at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computing in Croatia and if you go to his blog, Patakk, you can see a full bouquet of his latest creations. Some of them — the ones I use here to talk about biology — are his invented forms elegantly looped; he's also got some that spring out of nowhere, others that play with already existing images, making them shudder, scramble, break apart. He says he's relatively new to digital art and animation, mostly self-taught it seems, and feeling his way, but with every month, he just gets better and better and better.

Printing Out a Biological Machine

Incredibly Shrinking Avocados: Why This Year's Fruit Are So Tiny

We found lots of avocados being sold six or 10 to a $1 bag in the San Francisco area. Some weighed less than 3 ounces.

Alastair Bland for NPR We found lots of avocados being sold six or 10 to a $1 bag in the San Francisco area. Some weighed less than 3 ounces.Alastair Bland for NPR

We found lots of avocados being sold six or 10 to a $1 bag in the San Francisco area. Some weighed less than 3 ounces.Alastair Bland for NPR What's thick-skinned and leathery, about the size of an egg, essential for guacamole and sold eight for a dollar?

No, not limes. Hass avocados. This year, anyway. These pear-sized fruits usually weigh half a pound or more. In the summer of 2013, though, hundreds of thousands of trees in Southern California are sagging with the tiniest Hass avocados in local memory — some just the size of a golf ball.

The main reason for the lemon-sized fruits, sources say, is a very unusual growing year that consisted of low winter rainfall in early 2012 (avocados spend more than a full year developing on the tree), erratic bee activity during the late spring bloom period, and lots of unseasonably cool and cloudy weather in the year since.

"I can't ever remember a season when all the avocados were this small, and that's over 30 years in the business," says Charley Wolk, a farmer with orchards in San Diego and Riverside counties. He cites a lack of rain and late pollination back in the spring of 2012 as main factors in the little avocados.

By most accounts, the fruits are about 30 percent smaller than usual. "That means less per pound wholesale," Wolk says.

Avocados larger or smaller than what is considered normal are generally less attractive to consumers, he says, and, therefore, command less money per pound. He says about 8 ounces is the optimal — and average — weight of a California Hass. A 25-pound case of such fruits usually draws $1.20 per pound, according to Wolk. With each ounce less in average fruit size, the per-pound rate can drop by 30 cents, he says.

But the positive trade-off is that this year's crop consists of more individual fruits than usual and, in fact, will probably weigh in at more than usual. Wolk says a half-billion pounds of fruit are expected by the end of October. Most years, the California avocado harvest — 95 percent of which is of the Hass variety — tips the scales at around 400 million pounds.

Gary Bender, a University of California avocado specialist and farm adviser in San Diego County, says that most years, several months after pollination, high July temperatures cause many fruits to drop off the branches. That didn't occur in the summer of 2012. The resulting abundance of individual fruits on each tree, combined with low rainfall, cool temperatures and sluggish photosynthesizing, has likely caused the stunting. Bender says that in 29 years on the job he has not seen such tiny avocados as those being picked this year.

Several growers told The Salt that 2013's avocados are weighing mostly 5 to 6 ounces — but that could be a generous overestimate. We collected avocados at several randomly selected grocery stores in San Francisco, and at each location — all independent, Asian-American owned shops — we found numerous avocados, being sold six or 10 to a $1 bag, that weighed in at less than 3 ounces, and several less than 2.

"That's just ridiculous," Bender notes.

This season's avocados are the smallest in memory. We found some that were as tiny as 47 grams.

Alastair Bland/for NPR This season's avocados are the smallest in memory. We found some that were as tiny as 47 grams.Alastair Bland/for NPR

This season's avocados are the smallest in memory. We found some that were as tiny as 47 grams.Alastair Bland/for NPR Jim Donovan, with the Mission Produce Company, a fruit wholesaler in Oxnard, says that harvesting 2-ounce fruits is likeliest to occur toward the end of the picking season, which wraps up in the fall.

Some growers, he explains, may selectively harvest bigger avocados all season and meanwhile wait for the smaller ones to grow larger. Avocados, unlike other fruits, can continue to gain size for months until they are picked.

"But eventually the farmer can't wait any longer because the tree will drop the fruit, so they do what we call a 'strip-pick,' and take every avocado left hanging," Donovan says. These tiny fruits may draw less than half the wholesale price of normal-sized avocados. Cases of exceptionally large avocados — sometimes 14 or 16 ounces each — can also draw less per pound, he says.

Elisabeth Silva, San Diego County's agricultural crime prosecutor who deals every year in a number of avocado theft cases, says there could be foul play behind the sudden flood of tiny avos. She describes a sly method of insider theft by which harvesting crews sometimes receive orders to pick only fruits larger than a certain size.

"So, sometimes they'll put those bigger fruits in the bins and they'll skim off the undersized fruits for themselves and sell them on the side," Silva says. These, she adds, can get "laundered into legitimate commerce." She says that while tiny avocados, sold in unmarked bags, could very well be stolen, grocers generally have no role in, or knowledge of, such illicit activity.

Farmers and other fans of bigger avocados may get relief next year when industry experts expect this spring's relatively low number of newly set fruits to result in fewer but larger avocados. Meanwhile, the little avocados of 2013 won't hurt you a bit. Donovan at Mission Produce points out that size and price may be down, but that quality is just fine.

"If you're willing to cut 10 pieces instead of two to make your guacamole, then you've got a bargain," he says.

The Week: Progress in Quest for a Reusable Rocket, and Teleporting Data

Gulf Spill Sampling Questioned

Rome’s Start to Architectural Hubris

Lyme Disease Far More Common Than Previously Known

Black-legged ticks like this can transmit the bacterium that causes Lyme disease.

CDC Black-legged ticks like this can transmit the bacterium that causes Lyme disease.CDC

Black-legged ticks like this can transmit the bacterium that causes Lyme disease.CDC The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says 300,000 Americans are getting Lyme disease every year, and the toll is growing.

"It confirms what we've thought for a long time: This is a large problem," Dr. Paul Mead tells Shots. "The bottom line is that by defining how big the problem is we make it easier for everyone to figure out what kind of resources we have to use to address it."

Mead, who directs Lyme disease surveillance for the CDC, presented the new "preliminary" estimate at an international conference in Boston on Lyme and other tick-borne diseases.

The CDC says only a 10th of Lyme disease cases — fewer than 30,000 — are reported. And to make it more complicated, an unknown number of people are being diagnosed with Lyme disease who don't really have it.

The new estimate comes from three different ways of looking at the problem. CDC scientists analyzed insurance claims for 22 million people over six years. They surveyed labs that test for Lyme disease, and they did surveys asking people if they'd had the disease.

The result adds up to a vexing public health problem, all caused by a tick that's about the size of the period on the end of this sentence.

A generation ago there was no such thing called Lyme disease, though it may have been lurking undetected in nature. Scientists first reported it in 1977 and named it after the location of the first cases, in Lyme, Conn.

Now it's the most prevalent tick-borne infection — concentrated in 13 states in the Northeast and upper Midwest, but expanding both northward (to upper New York state and Maine) and southward (to Virginia).

In many areas where Lyme disease is entrenched, Mead says, up to 30 percent of black-legged or deer ticks carry the Lyme disease spirochete. That translates to a substantial risk of infection for humans who venture outdoors, especially in grassy and woodsy areas.

Getting Lyme disease is no picnic. Symptoms resemble the flu — fatigue, headache, mildly stiff neck, joint and muscle aches, and fever. But if not treated with an antibiotic within about 72 hours, the infection can disseminate throughout the body, causing neurologic, cardiac and joint disease for weeks or months.

An unknown proportion of Lyme disease patients become chronically ill with fatigue that can be debilitating. Mead says the CDC recognizes chronic Lyme disease as a real problem. "The question is whether it's due to persistent infection or some immunologic effect, and what's the best way of treating it," he says.

People often don't know when they have gotten Lyme disease. One tell-tale sign is a bulls-eye rash around the tick bite. But Mead says 20 or 30 percent of people don't get the rash — or don't recognize it because it's on their scalp or somewhere they can't see.

"So it's important for physicians to have a high level of suspicion" when they see someone with flu-like symptoms in summer, when there's not much real flu around, Mead says.

It's mainly up to residents of Lyme disease hot spots to avoid getting it — by using insect repellents, covering up when going outdoors and checking themselves for ticks when they get back inside.

Before 2002, humans could get vaccinated against Lyme disease (dogs still can). But the manufacturer discontinued it for lack of demand.

Mead acknowledges it's pretty hard to spot an insect that's no bigger than a poppy seed — much smaller than the common dog tick. "That's one of the reasons we encourage people to shower after being in a tick-infested area," he says. Studies show that showering within two hours after being outside sharply reduces the risk of infection.

One thing in humans' favor: The deer tick has to suck your blood for around 36 hours before the Lyme disease organism is transmitted. So gently removing the tick with tweezers, or — better yet — washing it off before it sinks its tiny fangs into your skin is the best way to win this game.

Observatory: 160-Million-Year-Old Fossil of an Omnivore

Chemical Composition of Urine

Allied troops in World War I were supplied with masks equipped with cotton pads soaked in urine because it was believed the ammonia in the urine would neutralize the chlorine gas used by German soldiers. Chlorine dissolves in the water portion of the urine, reacting with urea to form dichlorourea. While I'm sure you'd rather have an actual gas mask in the event you are exposed to chlorine, now you know how to make your own emergency filter.

Sunday, 18 August 2013

Plan to Ban Oil Drilling in Amazon Is Dropped

Star of NASA Planet Hunting Falls Idle With Broken Parts

Chevrolet’s Cheap Minicar, the Spark, Is a Surprisingly Strong Seller

Arid Southwest Cities’ Plea: Lose the Lawn

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: August 14, 2013

An article on Monday about communities across the Southwest that offer incentives to homeowners to replace their lawns with drought-resistant plants misstated the rebate prices in Los Angeles per square foot of grass removed. The city raised its rebate to $2 from $1.50 a square foot, not $2.50 from $2.

Latest SpaceX Rocket Test Successfully Goes Sideways

World Briefing | The Americas: A Mammal Long Overlooked, but Now Embraced

Lawmakers are lining up for a chance to take money from the banks — and do their bidding.

Lawmakers are lining up for a chance to take money from the banks — and do their bidding.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a fan of opera, which, like the court, wrestles with questions of crime and punishment.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a fan of opera, which, like the court, wrestles with questions of crime and punishment.How to Share Scientific Data

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: August 15, 2013

An article on Tuesday about the challenges of storing and making vast amounts of scientific data, much of it publicly financed, readily available referred incompletely to instructions from John P. Holdren, director of the federal Office of Science and Technology Policy, in a memorandum sent to federal agencies in February. While the memo said a guideline for making research papers publicly available would be an embargo period of a year after publication, it also stipulated that individual agencies could tailor their plans to release papers on a different time frame.